sunset junction

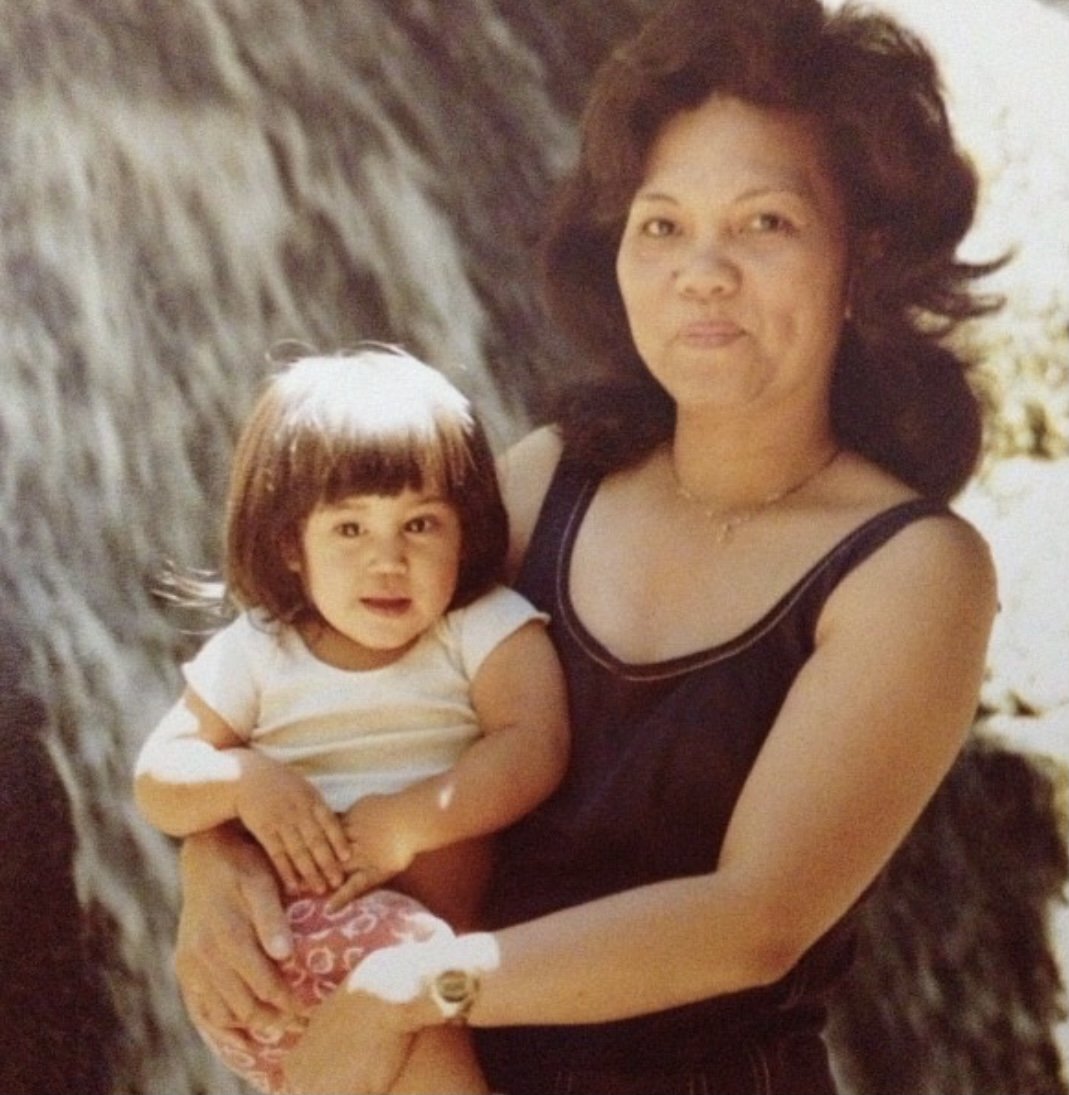

Baby Jenny with her mom in 1980's Los Angeles

As a kid, I didn’t fully understand why women went on walks. Early in the morning, to beat the summer heat, my mom would meet up with a friend or neighbor to walk around the block and surrounding cookie-cutter cul de sacs. What’s the point? I used to wonder. However, as an adult, I completely understand that going for a walk with a girlfriend is a necessary pastime. It offers space to be present in motion, breathing in fresh(ish) air so you can really catch up about all of life’s updates, wins, frustrations, etc. One of my favorite people to take walks with is Jennifer Castillo, a dear friend of mine who is a ride-or-die Angeleno.

Jenny and I used to see each other every single day for four years when we worked together at Paramount. She was my work wife/older sister figure, guiding me as I adjusted to being a baby adult living and working in LA – we met when I was 21, yikes! We recently caught up at our go-to walking spot, the Silver Lake Reservoir, which in Jenny’s case, is more than just a trendy eastside landmark. It’s basically her childhood backyard.

Jenny's walking buddy Yoshi

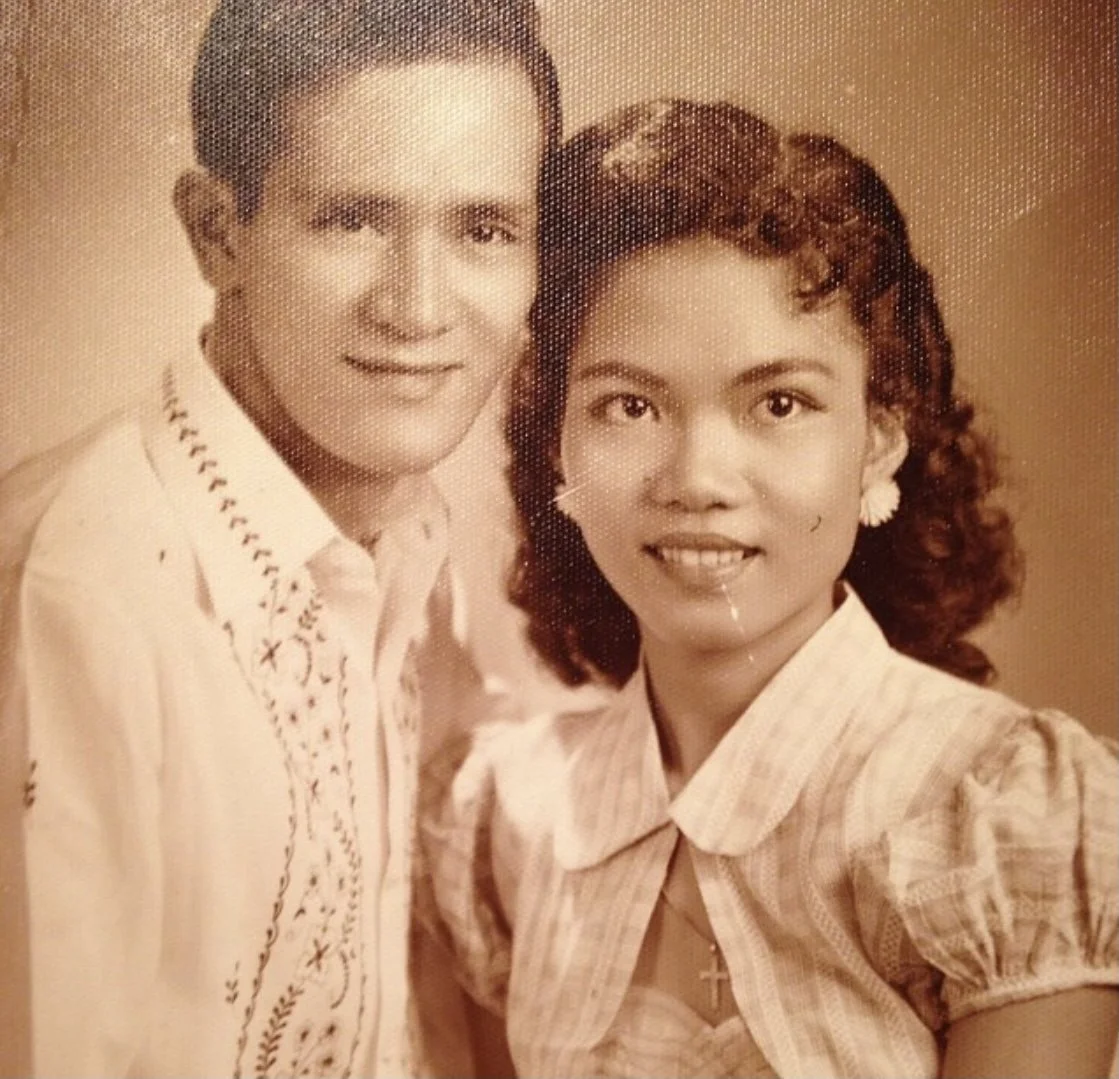

Jenny’s maternal grandmother used to own a 3-story craftsman on Maltman Avenue, a hilly street off of the infamous Sunset Boulevard in Silver Lake, arguably one of LA’s hippest neighborhoods. She first arrived in the States in the 1960s, finding Filipinotown, an enclave that sits south of the 101 freeway to Beverly Blvd, a hop and a skip from downtown Los Angeles. She brought her three young children with her, one of which is Jenny’s mother Caroline née Uson, leaving behind the Philippines after her husband passed away. Caroline attended Thomas Starr King Middle School and Marshall High School (where Grease was filmed) both of which I lived five minutes away from for several years. This “cool”, heavily gentrified neighborhood that prides itself on being home to the artsier folk of LA was my friend’s mom’s old stomping grounds!

Fast forward to Caroline meeting Jenny’s father Henry Castillo, a California native of Mexican, Spanish and Native American descent. They started a family, raising Jenny and her siblings in a duplex behind Los Globos, an essential staple to the LA club scene, where she lived during early childhood. Jenny recalls what her formative Silver Lake years taught her, how she’s grown to embrace being mixed and how she finds pride in the complexities she faces as a multicultural American.

Mikki: Why did your parents leave Silver Lake? It's so wild that they lived behind Los Globos.

Jenny: The reason why my parents moved was that they had three young kids under the age of twelve and the public system, LAUSD, at the time was terrible. When I was at Micheltorena [Elementary School] I was constantly getting into fights with kids because I didn’t speak Tagalog and I didn’t speak Spanish. I didn't fit in and at the time, there were a lot of...like, racial issues...

M: There were a lot of gangs too, right?

J: There were a lot of gangs, yes. I kept getting into fights. Kids would hit me. And then my sister would get into fights because she had the same issue. She didn’t speak Tagalog. She didn’t speak Spanish. So my parents were like, we can’t afford to send three kids here. We moved to La Verne because my uncle lived out there. He said it was a really good community and they have really good schools. I remember from growing up around here, my dad took us to Sunset Junction and Sunset Junction used to be for like... gay bondage.

M: I was just gonna say, super gay right? Like it’s where the bears would have their festivals.

J: It was super bear heavy and I remember seeing a guy wearing a collar being walked and I said, “Dad, why are they being walked? Why are they being kissed?” And my dad would say, “They can’t help it. That’s who they love.” So I was very much exposed to the LBGTQ community at a very young age.

M: I love it. I remember you talking about seeing Pride for the first time at Sunset Junction which is so cool.

J: Yeah, I was like a four or five-year-old kid.

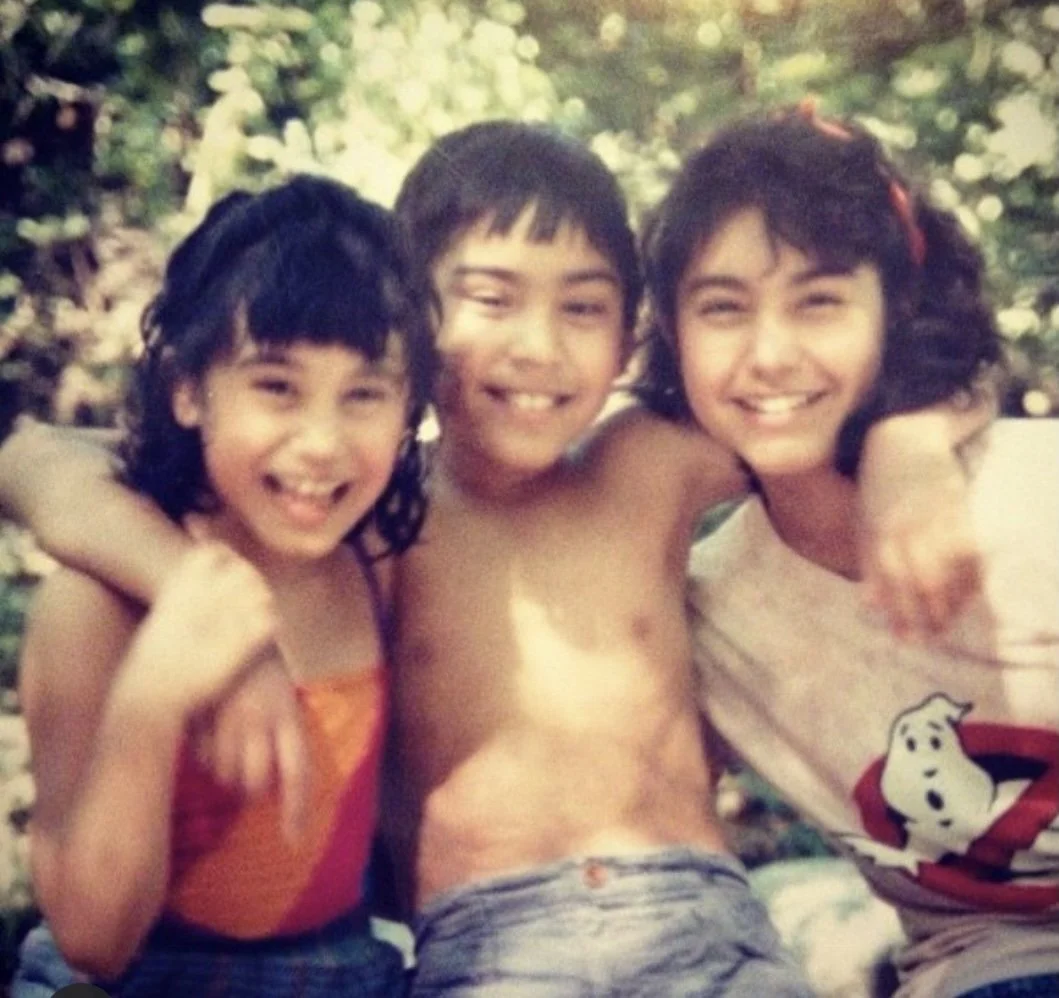

Summer fun with the Castillos

M: So you would come back and spend weekends with your grandmother?

J: I would spend weekends with my grandmother either at her house on Maltman Ave or her house in Atwater. And Atwater was predominantly a Latino neighborhood. And then... it’s changed.

M: Yeah! I don’t want you to speak for your family, but how do they feel about what’s happened?

Quick note: Both Silver Lake and Atwater Village have been highly gentrified in the last 20 years where it’s “normal” for a 2-bedroom house to sell for well over 1 million dollars. And what’s even more cringe, is that the current neighborhood fare goes viral when someone is seen shopping at Erewhon, a grossly overpriced market, cladding a BDSM look. Someone, please tell these people they are not as cool as the OG bears from back in the day.

J: Well, my grandmother, from my Filipino side, has nine siblings and they lived all over in Echo Park and Silver Lake. Out of all of my great aunts and uncles, two of them still have property out here and they’ve passed it on to their children. So they are very happy living in Silver Lake and Echo Park because it’s hip.

It is good in the sense that their families can still really enjoy those properties with it now being such a nicer neighborhood with cafes and restaurants down the street. When we were down here it wasn’t like that. It wasn't necessarily safe to walk after dark or to walk along Sunset Blvd. Millie's was always at the corner, and then the 99 Cent Store popped up probably in the ‘90s, like ‘93, ‘94. It’s completely changed. I wish my grandmother still had that house on Maltman because I would be set.

M: Totally.

J: There’s a Filipino bakery at the corner called United and it’s one of the oldest Filipino bakeries in the neighborhood. To me, when I drive by there, that’s the last surviving relic of how it used to be. When my grandmother is in town, she still wants to go and they know her there. So it is good and it is bad. Because there are a lot of cool places and it’s safer. But my family today would not have been able to afford it.

Photo credit: United Bread & Pastry, Inc.

M: Yeah. Growing up, how did you feel about being both Filipino and Mexican? Did you see that mix in other people, or was it not a big deal to you because you had your family to relate to?

J: When we first moved here, I was surrounded by a lot of diversity but I always wanted to assimilate because I just felt like I stuck out so much. My grade school friends were predominantly white. When I had friends over, they didn't understand the food my mom was cooking. My mom would cook everything but we would always have some type of Filipino dish or rice at every meal. They would have hot dogs or chicken tenders.

But in junior high, I started to befriend other people who looked like me. It was nice because when they would come over to my house, they would understand the food. When I went to their house, I understood the sense of respect that you have for your elders. I’d know how to approach their mom.

M: And there was a level of etiquette, not in a stuffy way but in a respectful way.

J: Yes. I should always offer to help with the dishes afterward. I should call their parents either tiya or ate. They are your elders, they live longer. You have to respect them.

Then in high school, all of my friends were like me: mixed. But we were the ten kids in school who were not white. And it really wasn’t until I came back out here, back in ‘99 when I started interning at Paramount that I was like, “Oh my god. I’m the only person of color again.” And then even later on, I was like, “I am the only brown person in this room.”

M: Did you feel those feelings again of trying to assimilate? Because even back then, diversity wasn’t really embraced.

Young Jenny and her mom

J: I always talked to my mom about this. When she was younger she always tried to assimilate. Even growing up in a very diverse area, she felt like she had to assimilate to American culture. And I always felt like that. When I was interning and working, I couldn’t bring my stinky food. I had to bring my sandwiches and assimilate versus saying, “No I’m gonna bring this.”

It wasn’t until probably my thirties when I was like, “I’m gonna embrace who I am and this is what makes me different and beautiful.” I think for me, it was when I traveled down to Santiago, Chile. Someone said to me, “Are you Mexican?” And I said, “Yes, I am Mexican.” And they said, “You should be proud of being Mexican because Mexico is a wonderful country.” And I didn’t really appreciate that until then.

M: I totally relate to that. I didn’t like being Mexican growing up and I was always a little shady towards embracing it. Until I went to Mexico for leisure and not on a creepy missions trip. But when I finally went to Mexico City and Tulum and all these places, I’m like, Mexico is one of the best countries in the world and it’s so sad that traditional America doesn’t get it.

J: They don’t appreciate Mexican culture and what they have brought to America. For my 40th birthday, I went to Mexico City and I had a moment when I got really emotional because I was just so in awe of the culture, the food, the architecture, the sophistication and I just felt this overwhelming sense of pride knowing this is where my ancestors are from. This is the culture, this is where they’re from.

The reason why I have a major disconnect [to her Mexican side], is because my dad's family has been in California forever. They don’t have a sense of attachment towards Mexico. All of their traditions are America-based, not Mexico-based. They don’t celebrate their Mexican side. They celebrate being American. Versus growing up Filipino, I'm first-generation American. I was still so close to that culture.

M: Have you visited the Philippines?

J: I haven’t been to the Philippines but I think that’s an important trip I have to take. Probably next year.

M: What are our thoughts regarding strategies for people trying to learn how to be more cultural and accepting of other people?

J: Go visit a country and live with a local family. And if you can't afford to do that, I think to really teach diversity, you have to teach it at a really young age. There needs to be more classes on ethnic studies. Each class in grade school needs to be like we’re learning about Filipino culture, we’re learning about Mexican culture and we’re learning about this and this because you really do learn it at a young age. And I think we need to re-educate adults. And we need to change our U.S. history to include all the things that America has done. We basically abolished Native Americans... I think even going to a new restaurant, trying a new restaurant. I know when I first had crickets…

M: I love crickets.

J: I was like, oh I’m scared, but I had them and I was happy I did it. And yes I did grow up eating some weird food. But that’s a great way to learn about a culture.

M: What are some of your favorite Filipino dishes?

J: I love pancít, which is a noodle dish and it’s made of thin glass noodles. Lumpia which is a fried egg roll type of dish and Arroz Caldo which is basically a rice dish but it's kind of like a porridge and it's made with ginger and chicken and my grandmother would make it when we were sick. So it's a comfort food.

M: What is your relationship to language now?

J: I want to learn more Spanish.

M: Same, always.

J: This was the best advice my best friend gave me. She was teaching in Santiago and she said you need to learn the basics. Learn how to ask certain questions and learn the numbers because it’s not right to go to a new country and expect them to speak English. You have to respect that culture and respect their language. So I always try to learn a few things for all the countries I've gone to even though I don't necessarily know the language, but I always try. But I want to learn more Spanish. I can read it and if I'm in Mexico and they speak slowly enough to me, then I can piece it together. So my next step is to become more conversational. I don't have to master it but I need to learn more of it. And I do understand some Tagalog. Tagalog and Spanish, a lot of the words are very similar.

Jenny and her husband Josh in Prague

Santa Barbara summer wedding

M: What does your friend group look like now as an adult?

J: I have a very diverse group of friends.

M: I love when people say that! Everyone needs a diverse group of friends.

J: All of my friends are pretty progressive. I would consider them like the Bernie Sanders group.

M: Hell yeah.

J: They’re people of color from all different economic backgrounds. All colors, all sexual orientations, pretty diverse.

M: How do you think that has added to your life?

J: It just helps me become more empathetic and understand my life compared to theirs. It makes me more compassionate.

M: What are you passionate about?

J: One thing I think about a lot is when we worked at Paramount and how we didn’t have any support. I think we really need to change Hollywood. Working from the corporate studio to production. And offering more mentorship. And you know I love wine and I want to work in the wine industry and one thing I've been trying to do is support people of color and female-owned wineries and companies that give back to their employees, that really fight for them.

Jennifer's Top Wineries to Support

Copia Vineyards and Winery - Paso Robles winery owned by Indian American couple Varinder and Anita Sahi

Desperada Wines - Woman-owned winemaker in Paso Robles

Stolpman Vineyards - Ballard Canyon winery that hires their farm workers full-time, year-round and provides an opportunity for them to make their own wine, La Cuadrilla, with profits going directly back to them. They also hosted vaccination clinics to get the workers of Santa Ynez vaccinated.